We need to talk about coffee | Caffeine Magazine | Issue 31

Coffee communicates – in the Middle East. If you’ve ever attempted to trace the origins of coffee and the first discovery of its elixerial, stimulant properties, you’ll come across a cacophony of legends. As a subject of exploration, it has more plots, twists and turns than Game of Thrones. You’ll have no doubt heard well-yarned stories involving Sufi mystics observing birds of unusually high energy; a chap called Omar – a banished healer who ate the berries in Yemen and tried roasting them, leading to his being exalted as a saint for this miraculous discovery; or, a goat herder called Kaldi who noticed the effects on his own flock and decided to give the berries a try.

From stories of coffee’s arrival in the Middle East, and onwards to India, South East Asia, Europe and the Americas, you’ll infrequently encounter tales of slaves travelling to Yemen from Ethiopia, through Mocha. Or, mentions within the Sufi monasteries of Yemen; the coffee houses of Cairo; into early manuscripts; and finally through Istanbul, the capital of the vast Ottoman Turkish Empire (from circa 1299). The Gulf’s own fascination with coffee stretches well back into the bowels of history, from Arabic philosophers who wrote about coffee in 800 to 900AD to claims that coffee originated from the Arabian Peninsula itself, cultivated in Yemen from around 575AD. Other stories claim coffee spread to Yemen through Sudanese slaves – believed to have eaten beans to help them stay alive as they rowed ships across the Red Sea between Africa and the Arabian Peninsula*.

[*Walter Miyanari, Aloha from Coffee Island, Savant Books and Publications, 2013]

Amongst all these delightfully distracting tales, we can almost certainly confirm that coffee was primarily consumed in the Islamic world where it originated and was directly related to religious practices**. What is definitely known is that ancient Yemeni clay brewing pots are older than the Western word ‘coffee’. The word qahwa originally meant wine, and Sufis in Yemen are recorded as using the beverage as an aid to concentration and a form of spiritual intoxication when chanting the name of God***.

[**Grigg, David, 2002, The worlds of tea and coffee: Patterns of consumption. GeoJournal. 57 (4): 283–294.]

[***http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-22190802]

This cause and effect of religion on the dispersion of coffee can’t be ignored. As the Qu’ran forbids Muslims from drinking alcohol, coffee continues to be a popular alternative in Islamic countries today – both for its stimulating effects and for the convivial, socialising function that wine might provide elsewhere. The first coffeehouses established in Mecca were known as the Kaveh Kanes, public places where Muslims could socialize and discuss religious matters. Despite illicit moments, when coffee was banned in Mecca, Cairo and Ethiopia, the use of coffee continued to be widespread throughout Arabia, North Africa and Turkey. Its nutritional benefits thought to be so great that it was considered as important as bread and water – so much so that, purportedly, a law was passed in Saudi making it grounds for divorce if a husband refused his wife coffee*.

[*http://metro.co.uk/2015/10/23/11-of-the-most-bizarre-divorce-laws-from-around-the-world-including-killing-a-cheating-spouse-5458115/]

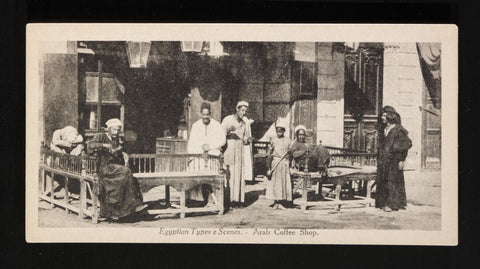

Postcard, Men standing in front patio of a shop (Egyptian Types e Scenes - Arab Coffee Shop), M. Castro, From the collection of Dr. Paula Sanders, Rice University. Castro, M. [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons

When you try to pinpoint coffee’s role in the Middle East, through conversation, through questions, you’ll invariably receive a smile, a nod and then another distinctive tale of where, how and what is so important about it. Yet, each story takes us almost always back to the source, the historic crossroads of trade through the world.

In this way, and perhaps in keeping with the oral traditions of the region, coffee in the Middle East communicates. Of course, the beans themselves are not conversing, it is the act of making, drinking and sharing coffee, with its own rituals and symbolism that speaks across generations and cultures. Rock your cup from side to side and you’re signalling to your host that you’ve had enough. Hold your cup whilst coffee is poured, and place it on the table in front of you without taking a sip, and you have come to discuss something, you have something to ask of your host. Invariably this will illicit a ‘how can I help you?’ or a ‘what do you want?’ or, perhaps, given the context of recent press on speciality coffee in Dubai – a ‘we need to talk’. Many an engagement has been confirmed in this way, many a business proposition discussed. In fact, coffee is the first sign of Arab hospitality – whenever you visit anyone in the Arab world, the first thing you will be offered is coffee. We’re not talking ‘a coffee’, but coffee on tap, from an ornate flask or dallah into a small qaddah (cup) for as long as you can drink it.

“Coffee is the common man’s gold,

and like gold it brings to every person

the feeling of luxury and nobility.”

(Shaykh Abd al–Kadir 1588)*

[*Shaykh Abd al–Kadir wrote the earliest known manuscript on the history of coffee in 1588]

Whether it’s Turkish or Arabic – beware of confusing the two, the making and serving of each are very distinct things – all is bound up in ritual and in the case of Turkish coffee, with superstition. For coffee in some instances not only communicates, it can also be read**.

[**Known as tasseography, Turkish coffee fortune telling is done through the muddy sediment left at the bottom of the cup and is recorded as early as the 16th century. Fortune telling is illegal in parts of the Middle East.]

Much like the arguments around tales that enshrine coffee’s origins, tying the bean to the region – which are true, which are fable – so too are there myriad ways to prepare your Arabic brew. Below just two:

- Put 3 cups of water in a pot and bring to a just foaming

- Add the coffee grounds and heat over low flame

- Pour the coffee into a kettle, leaving the coffee to settle in the pot

- Add in the cardamom and saffron to the kettle of coffee and bring to just bubbling – twice – before serving in small cups

Or perhaps

- Warm coffee grounds (roasted just past first colour change) on low heat

- Add water and heat to foam for3–4 minutes

- Remove from heat and allow coffee to settle

- Filter

- Add cardamom (or you may want to stir in mastic sap)

- Heat up once again, simmer 20 minutes

- Serve in small cups

Edward William Lane, 1801-1876, "An Account of the Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians, Written in Egypt During the Years 1833, -34, and -35, Partly from Notes Made During a Former Visit to that Country in the Years 1825, -26, -27, and -28. Volume 1". Charles Knight & Co.: London, 1836. p 169.

CC BY-SA 2.5 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons

These tweaks, changes, preferences, are pinned to the individual. You make your own choice, your own mind. Whilst in the UAE, we learnt several ever so slightly varying ways to brew a cup. Change, diversity, learning your own preferences – it seems – can only happen through conversation, through learning. Can perhaps only truly be progressed through a process of exchange. And negotiation may only be made through the sharing from one person with another, over a cup of brew.

We arrived in the Middle East over six years ago. We’d anticipated and imagined halcyon scenes of old Arabic coffee houses. Instead, we were welcomed into a world of burgeoning speciality, embedded within tradition. With many locals having spent time abroad, the influence of exposure to new approaches to coffee is undeniable, but it is seeded within already developed nuances – these are innovations chosen to enhance an innate, homegrown tradition, not the wholesale importing of a trend from elsewhere. In terms of where and how speciality is found, it’s true that within many traditional Arabic cafés or eateries, the option for a separate ‘family room’ for men and women is still an option. But, within more recent and contemporary spaces you’ll find a broad cultural pool of locals, Western and South Asian expats, to name a few. Ideas of sex-segregated spaces, ethnically focused locales are uncommon. Imagine instead sites where alcohol is prohibited opening up unique possibilities for our energy-inducing vibrant friend, coffee.

Ratios, Sharjah

To take the UAE as an example, location diversity is abundant. From converted warehouses of the industrial districts – think eccentric, atmospheric heavy metal and motorbikes with Café Moto and the more clean cut roastery/bike shop Café Rider, or the speciality fine-tuned roastery-come-café spaces of Nightjar and Seven Fortunes. Or, nestled on the ground floor of a luxury hotel tower is speciality café, roastery and bakery The Sum of Us, the home of Encounter Coffee led by Jamie Elfman. An hour north-east and situated in the heart of Sharjah, within the historical souq district is Ratios. Using material reclaimed from a Dhow, this space could be the embodiment what coffee is today in the Middle East. Founded by Emirati Khalid Al Qassimi, the space fuses tradition and the contemporary, using the sight, smell and touch of this 60 year-old well-worn re-purposed boat – a vessel that spent decades travelling ancient trade routes – to fit out the space. Offering the best speciality coffee from roasters in the region, their focus is all on coffee with no dilution. In these contexts, any Western misconceptions of restricted, surveilled Middle Eastern lives are put to rest. These are multi-cultural, all-gender, open spaces to meet. It is true, within many cultures, drinking coffee is very much about the ritual and ceremony. Yet, when compared, Western coffee culture is more habitual than ceremonial (often a daily pick-me-up or dashed grab-and-go en route to work).

“Coffee and dates are the traditional welcome into someone’s home or establishment, this fact can begin to help to explain the exponential growth of specialty coffee in the region. Because the drinking of coffee is already so deeply entrenched in the culture, the arrival of specialty coffee on the scene wasn’t so much introducing something new as much as it was introducing just a new approach to a very old and established routine.” Antony Papandreou, Nightjar Coffee

Late into the night, crowds of local coffee drinkers can be seen at their favourite coffee spots – perhaps the absence of other mind-altering substances has helped solidify the importance of coffee culture in the region, specifically in a contemporary context. A nightcap in the Middle East is not a glass of wine, but a pot of coffee – locals gather in their local coffee shop in the same way that, elsewhere, the dregs of the evening are seen away in pubs.

With cafés and roasteries partnered often between locals and expats, the drive towards speciality may come from time spent abroad, knowledge exchanged and filtered back into the local community. Some areas within the region may be struggling to build on their own identity – rapid construction, recent conflict, influx of new cultures – ending up being quite heavily influenced by other, more established third wave coffee cultures. Yet, with the pace at which it is developing, it is not too hard to imagine a stage where creating from an innate cultural bed of knowledge occurs as opposed to something more akin to the mirroring of hipster levity – denim and leather aprons, albeit with beards that are the cultural norm, not hipster-aspirational here.

Coffee spaces, and speciality in particular, serve the same socialising, time-killing, friendship-solidifying purposes as bars. Whilst reverence for tradition is keen, locals educated abroad are far from being closed minded or ignorant with regards to social interactions. They are instead careful to observe local traditions with regard to socialising together – there are no restrictions, just social codes that you choose whether or not to live by.

“In my view social traditions or etiquettes don’t seem to have placed any inhibitions on enjoyment of good coffee. People pick their spots. There is a keen interest to learn too – roasting programmes are common, especially with many locals roasting at home. We have customers who buy speciality green coffee from us to roast at home for their family and friends.” Antony Papandreou, Nightjar Coffee

In this sense, the scene is socially progressive, and it seems strange that perhaps to a Western audience this needs to be made explicit – for it’s hard to imagine anyone who doesn’t know of someone who is living or working in the region.

Speciality and traditional approaches to coffee can often be seen to sit seamlessly in the Middle East. Not only are these spaces where cultures interact, gain exposure, simply meet – but they also somehow embody the ethos of the majlis. Literally meaning a ‘place of sitting’, they specifically mean a place to sit and talk – even to council level. Traditionally, these spaces were for men, but today they embody more an attitude to sharing, a space where everything and anything is on the table for discussion. Normally held within a private space, you’ll also find minimally more public majlis in studios or open outdoor spaces. For example, if invited to contemporary artist Ahmed Mater’s Pharan.Studio in Saudi, you’ll be served both traditional coffee or a selection of speciality coffees from local roasters. Here, each new batch of coffee is tested both through ibrik, Arabic style and through an espresso machine. This synthesis is domestic, social and professional – even to the level of speciality competitions which are not strictly held within commercially rented spaces as per the Western model – at recent Aeropress qualifiers, hosted in the heritage district of Dubai, judges sat in an open-air majlis.

Whilst parts of the Middle East are said to be impenetrable to the visitor, not necessarily in terms of visas or access, but more with regards to how to locate a local culture amid the high-rise tropes imported and imprinted from the West –coffee is as good a place to start as any, in fact, it may even take you straight to the heart. Because – coffee communicates, and perhaps, given space and notice to boil and calm, to only boil again before being served, will have a chance to play a role in communicating, negotiating, finding middle grounds for those who share common and open thought to meet. We need to talk about coffee – and there is a new wave of independent coffee shops and roasters bringing new ideas and merging these with tradition and ceremony in the Middle East. Here are some to check out, non-exhaustive – but perhaps a good place to start:

UAE: Coffee Museum (for a history), Nightjar Coffee, Seven Fortunes, Encounter Coffee, Ratios

Jordan: Dimitri’s Coffee

Turkey: Kronotrop, Petra, Probador Colectiva

Saudi: Brew 92, Camel Step

Lebanon: Kalei Coffee

Kuwait: Pause Coffee, Volume 1, Caffeine, Toby’s Estate

Iran: Sam Café, Roberto

Qatar: Flat White (workplace of the Turkish Barista Champion)

Yemen: Rayyan Mill, Qima Coffee